How Fast Twitch & Slow Twitch Muscle Fibers Are Different

Did you know that the muscle fibers in your body aren’t all the same?

In fact, you actually have several distinct types of muscle fibers, which are adapted for different forms of movement and exercise.

Many people know of these as ‘fast twitch’ and ‘slow twitch’ muscle fibers, but there tends to be quite a bit of confusion about what this really means and why it matters.

More importantly, are you somehow genetically limited, in terms of your ability to build strength and muscle, if you don’t have enough of the right types of muscle fibers?

Well, the truth is that while there are genetically determined differences in these muscle fibers, from person to person, it isn’t as big of a deal as you may think.

To help put things into perspective, in this article we’ll walk you through the 3 main types of muscle fibers in the human body, how this relates to working out and training, and if it’s possible to force your body to generate more of a certain type of muscle fiber.

Let’s get right into it.

What Are Muscle Fibers & How Do They Work?

To put things in a larger context, muscle fibers are part of what is known as our skeletal muscle system.

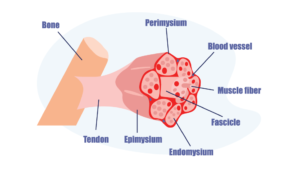

These muscle fibers are actually long strands of individual muscle cells, housed in a protective layer of connective tissue called perimysium.

Here is a diagram showing you what this looks like:

In each of your muscles, these muscle fibers will be organized into different bundles known as motor units.

Whenever you want to move a muscle in your body, your brain will instantantiously send a signal to make the cells in the appropriate motor unit contract.

If you are doing a less intensive activity – like combing your hair or typing on your computer – your brain will send a signal to motor units with a smaller number of muscle fibers.

Conversely, when you’re engaged in a higher intensity activity, such as lifting weights, your brain will also send impulses to motor units with a larger number of muscle fibers.

Now when your body recruits these muscle fibers, it does so sequentially.

That is to say, for any given activity, your body will start by recruiting the smallest motor units, containing the lowest number of muscle fibers – and will then progressively move up to larger motor units with a greater number of muscle fibers, based on the intensity required for the specific movement.

This means that if you’re trying to lift something that is particularly heavy, your body will attempt to recruit all of the available motor units in the relevant muscle groups.

It’s also interesting to note that when a muscle cell contracts, it contracts 100%; there are no granular degrees of contraction, so the amount of force generated is entirely dependent on the number of muscle fibers recruited and their specific type.

On that note, it turns out that there are actually 3 different types of muscle fibers that are found in humans.

These are:

- Type I muscle fibers

- Type IIa muscle fibers

- Type IIB muscle fibers

Type I fibers are what people tend to think of as slow twitch muscle fibers, whereas both variations of type II are fast twitch muscle fibers.

Let’s take a closer look at each type of fiber, and what activities they are best suited for.

Type I Muscle Fibers

Type I, slow twitch muscle fibers are capable of producing the lowest amount of force, have the least potential for growth, and also contract at the slowest speeds.

However, since they are rich in both mitochondria and myoglobin, the compound responsible for transporting oxygen, they are far more resistant to fatigue than type II fibers.

This makes them best suited to activities that require low amounts of muscle tension for extended periods of time.

For this reason, they tend to be found in higher concentrations in muscles that assist with posture, such as the neck, spinal muscles, and hip flexors.

Type IIa Muscle Fibers

Type IIa muscle fibers are a type of fast twitch fiber, contracting more quickly and capable of generating more force than type I fibers.

They also have a greater potential for growth than type I fibers.

At the same time, they still have a fairly large amount of mitochondria and myoglobin, making them somewhat resistant to fatigue (but not as resistant as type I fibers).

For this reason, they are best suited to longer-term anaerobic activities, like swimming, with moderate power demands.

Type IIb Muscle Fibers

You can think of type IIb fibers as being an even faster twitch vision of the type IIa fibers.

That is, type IIb fibers contract faster, and with greater force production, than either type I or type IIa fibers, making them the best suited for high intensity activities.

However, since they lack the mitochondria and myoglobin of the other types (making them white in color instead of red) they are also the most easily fatigued, and can only be used for relatively short periods of time.

How Muscle Fibers Relate To Working Out

So far, this article has covered a lot of theory, but now we’re going to bring it all back to what you’re probably most interested in…

That is, how all of this can impact your workouts, and help you build muscle and strength more effectively.

Well, as you have probably guessed by now, different types of muscle fibers are stimulated depending on the type of training that you’re doing.

If you focus more on strength training, lifting heavier weights for fewer repetitions, you’ll stimulate more of the Type II fibers.

Alternatively, if you focus more on endurance training, lifting lighter weights for more repetitions, you’ll stimulate more Type I fibers.

This confirms much of what I often talk about in my articles: that if you want to build both strength and muscle in the most effective way possible, your training should focus primarily on progressive heavy weight training at a lower number of repetitions.

On the other hand, if you’re an athlete that requires greater levels of muscle endurance, then training with lighter loads over a greater number of reps, focusing on movements that translate well into your particular sport, will stimulate more of the type I fibers.

In the end, which muscle fibers you should focus on all comes down to your training goals.

How To Get More Of A Certain Type Of Muscle Fiber

The short answer is that you can’t.

Genetics play a significant role in how many type I fibers you have relative to type II fibers

It also doesn’t seem likely that training actually increases the number of fibers, since studies have shown that fiber count doesn’t change with exercise.

However, this doesn’t mean that just because you happen to have fewer type II fibers that you shouldn’t be lifting heavy if you want to build strength and muscle.

That type of training is still the most effective if you want to build a lean, muscular body, regardless of your specific type II fiber count.

What’s more, research has shown that most people are only able to recruit around 50% of their motor units!

This means that even if you have a relatively smaller number of fast twitch muscle fibers, you still have significant room for improvement by training your body to recruit more of them effectively.

In fact, I would say that inadequate recruitment of type II muscle fibers is more of a limiting factor than genetics for many people.

Recruiting more muscle fibers simply comes down to consistently practicing each of your exercises, and allowing your body to gradually adapt and become more efficient with its neuromuscular connections.

This will result in you being able to recruit a greater percentage of your fast twitch muscle fibers, allowing you to lift more weight, get stronger, and build muscle more effectively.

The Bottom Line On Muscle Fibers

In conclusion, while understanding the characteristics of these different types of muscle fibers can help to inform the way you work out, you shouldn’t worry about it too much beyond that.

This means that you shouldn’t focus too much on your type II fiber count and allow it to put artificial limits on your training.

Sure, the best strength athletes in the world will generally be on the higher end of the type II muscle fiber count, but these are people that are operating at the peak of their genetic potential.

For most of us, there is a lot of room for improvement, even within these individual genetic constraints, so just focus on getting progressively better each week rather than dwelling on perceived limitations.